To kick off our April Generative Writing Workshops at Apiary Lit, and to commemorate the start of National Poetry Month, here are a few general Generative Writing Tips we gathered from our workshop instructors, and our friends in the writing community!

Kenzie Allen

- Keep a notebook, or even a notes file on a computer or phone, or a set of index cards folded up in your wallet (index cards are the best).

- Think about observation, participant observation, and generally training the brain toward composition through the act of observing and recording (and then transcribing, from notes to drafts, and then multiple rounds of revising) — think of it as one of those habits, like exercise, you’d like to develop.

- Try things. You’ll determine over time if you want to add them to your process or not. Don’t be afraid to collage, jumble things together, or start messing with syntax (perhaps or–perhaps not–in readable ways).

- Sometimes you’ll get stuck. Good to remember to be kind to yourself when this happens, or pivot, or find a way to take the pressure off (or switch to bones or smaller pieces or lists). — Just carry your notebook (/phone notes app, /both since they access different parts of the brain) with you and keep making observations. That act alone kinda tends to change the brain in such incredible ways, to fall more naturally into the act of composition. Making that a daily practice if it isn’t now, or making freewriting one, can really just sorta alter your brain (think of it like stretching and take the pressure off!).

- Keep a file folder for “daily work” (in the case of poetry or short pieces) — you may not always keep a daily practice of writing but having that folder encourages you to start making it a MORE daily habit — and it’s where your first drafts, essentially, can go, every time.

- Lists! Make lots of lists.

- When you’re putting together a piece of text, one approach is to free-write. Like stretching, it’s important to flex the muscles a bit, and clear the throat, if you will (or it may even be the case that the beginning of a poem/piece later turns out to be that “throat-clearing” or “runway” section that could be removed).

- For longer pieces, consider putting together a document or set of “bones” or simply things that feel and sound right, individual sentences or even phrasing, moments you know you want in there, things that encapsulate the mood and/or main moments or key sparks in sentences or small paragraphs. You can add in the connective tissue later — take the pressure off your generative mind, work in pieces, lists, and “bones.”

- Remember that you’ll have plenty of time to revise later, so take the luxury of exploration now.

Meredith Luby

- Write notes in your phone, then email them to yourself every week.

- also, listen to music in a language you do not speak

Chelsea Biondolillo

- (in response to Meredith’s tip about music): I use that^ tip for jogging. It works great. My play lists are made up of a bunch of dance music in languages I don’t speak. I slow down when I sing along, I think. (So, applied to one’s work — tempo, unfamiliarity or familiarity, various kinds of input.)

- places to make sure you have something to write on and write with (I have been given so many blank notebooks, so I just stash them all over): Bedside table – write that dream down as soon as you wake up! Your various bags, purses, backpacks–tailor the notebook or even index card to the size of the bag; On your desk – you may think, But my computer is on my desk! But sometimes you are doing one thing and suddenly think of a line of poetry or an opening sentence, and you don’t want to lose it or break your stride, so having post-its or a notepad nearby is useful; Your car — NOTE: Don’t try to write and drive – use your phone’s voice memos for that, but, what about those moments after you park or before you take off again?

- and also stash a notebook next to the seat or chair where you watch TV most often. Write down dialogue or weird lines from commercials for use later.

Vanessa Moody

- Ride public transportation for a while with a notebook and write down interesting bits of language, character descriptions, imaginary backstories. (people watch)

- Mini-peer-review: This tip is less for generating new pieces and more for unblocking when you’re stuck: find a friend who’s willing to chat with you for a little bit (fifteen minutes is really all you need) about your project. Try to explain to them in thirty seconds to a minute what your piece is about. Then, talk about the problem you’ve encountered that you can’t seem to get past. Have your friend 1) repeat back, in their own words, what your project is about and 2) ask you questions about the project related to the problem that is giving you writer’s block. A fresh perspective from a curious friend who asks the right questions can help to unblock you! Having to speak for your own work, without giving someone something to read, is a difficult task, but it is an important step to truly understanding your purpose in the project.

Sara Hovda, a poet in our Apiary Lit Workshops inaugural class, brought up the concept of rubber duck-debugging in response to Vanessa’s suggestion of mini-peer-review. We loved the idea of applying this concept and others to one’s work in the process of revision, and to the practice of articulating craft techniques.

Rebecca Hazelwood

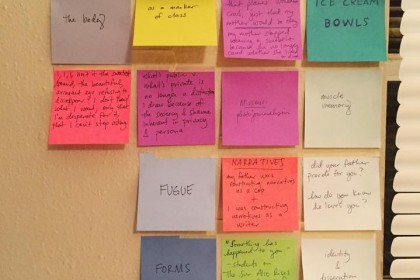

Rebecca is doing this fantastic thing with sticky notes.

“One of the best things about having my own office is being able to post visual reminders about what I’m writing about and what I’m writing for. This is my second wall of the year/semester, which has been brewing for the past week or two.”

Of her first round of post-its, she writes: “I put these notes on the wall because they were questions and concerns, preoccupations and obsessions I had based on feedback from my first readers and my own sense of what needed to happen. And I just left the post-it’s there for a couple of months so I’d see them enough that they’d sink in.”

We also like looking at notebook cheesecake when we need a good pick-me up. Just don’t let it pressure you out of writing–get it down, get it on the page somewhere!

We hope you find these tips helpful! Share your own tips in the comments, and go forth and generate new work, writerkindred!

There are still a few seats remaining in our Generative CNF and Generative Poetry workshops for the month of April! The courses go at your own pace, so there is still time to join us! (Registration will remain open until Friday, April 3, at noon EST.)

Or check back with us this summer for these workshops and more!